Our Heritage

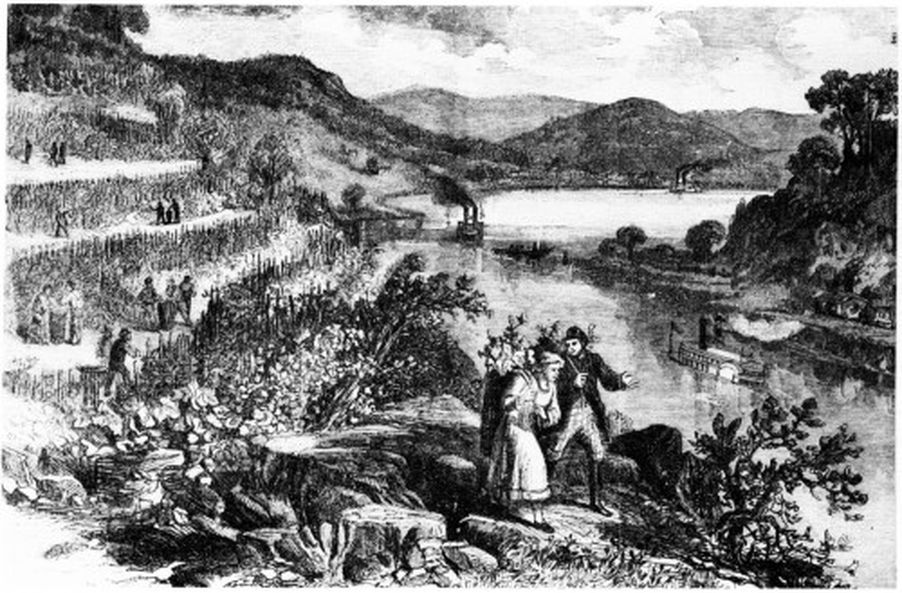

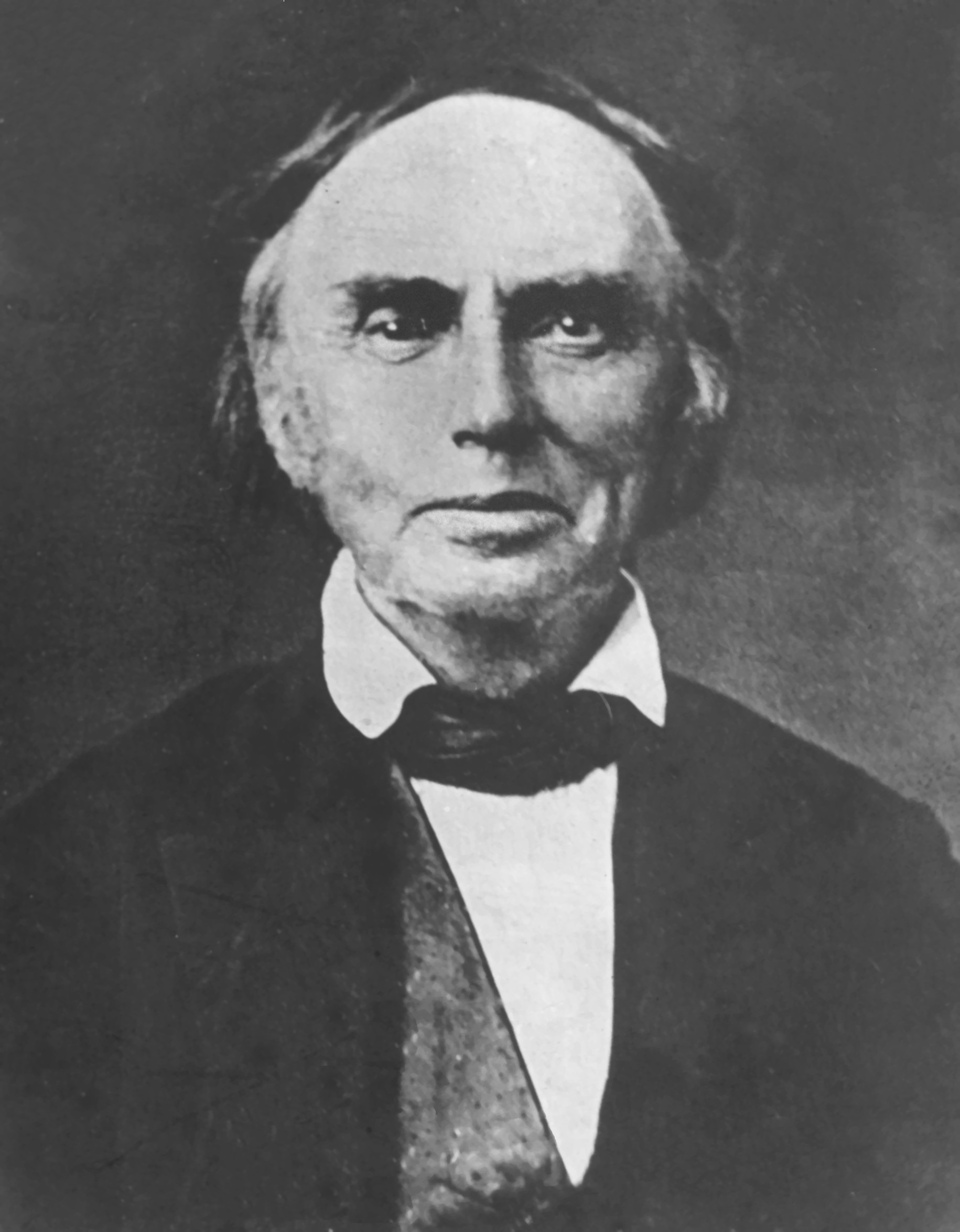

In the 1800’s this region was known for its wine production. From Mt. Adams and on both sides of the Ohio River, growers like Nicholas Longworth had numerous vineyards of note. By 1860 the state of Ohio was supplying one-third of the nation’s wine; Longworth alone had 2,000 acres under vine and was producing more than 100,000 bottles annually. By all accounts, Nicholas Longworth was the father of American wine and Ohio was the epicenter of American winemaking. So much so, that we have our own named wine growing region, The Ohio River Valley Appellation.

Today, in that same spirit, the local wine industry is making a major comeback in Ohio and Kentucky, and Seconda Volta Vineyards is part of that movement. We grow our grapes with special care and because our vineyard is smaller we give each vine the special attention it needs to produce the very best grapes. We make no attempt to produce mass quantities of wine. Instead, we set high standards for quality and take our time to produce only the very best grapes and wine.

Historian Amanda Foreman, WSJ, searches the past for the origins champagne:

French wine producers have fought hard to protect the name of champagne. Since 1891, under the terms of the international Treaty of Madrid, only sparkling wines made in the eponymous region can be called champagne, as though the rest are impostors. But as corks go a-popping and glasses a-clinking this holiday season, we should remember the unsung, non-Gallic heroes who helped make it all possible.

In the U.S., the discovery of the catawba grape in 1802 opened the way to making native-grown wine. Nicholas Longworth, the father of American “champagne,” was already one of the richest men in the country when he set out to transform Cincinnati, Ohio, into the epicenter of the New World wine industry. His first sparkling wine was made quite by accident in 1842. It was so popular that eight years later Longworth’s winery was producing 60,000 bottles a year.

Sparkling catawba proved to be a short-lived affair, however. A disease called Black Rot caused most of Longworth’s vines to die, while the Civil War robbed him of the necessary manpower. But an even greater disaster awaited the French. The phylloxera, a vine-killing aphid-like insect, crossed the Atlantic during the 1860s, causing what is known as the Great French Wine Blight.

By the early 1900s the entire Champagne region was facing extinction. There was a cure, but to some French winemakers it seemed worse than the disease: grafting French vines onto certain American rootstocks made them impervious to phylloxera. The vineyards were saved.

Champagne may have its heart in France, but its brains are British, its strength American and its origins Roman. Cheers to one and all.